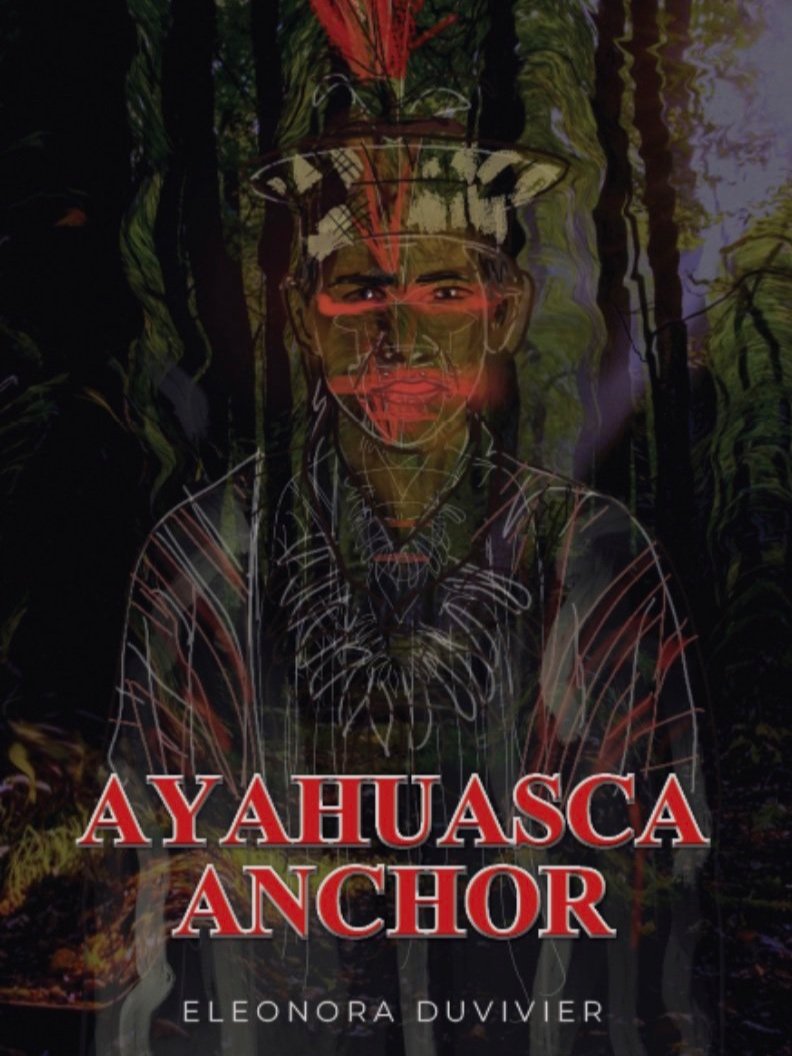

Ayahuasca Anchor

Written by Eleonora Duvivier

A signature short story from Eleonora Duvivier’s short story collection of the same title. To view the entire collection, click here.

My two children and I don’t have a common home of origin, for they were born in different countries and from different fathers. But when I met him, the Vine called us to the core of the forest and anchored us within.

Ayahuasca is a wave, the sea, and the love between them; the freedom to split and the mighty force of return that makes each cease to be for the sake of the other; of their communion. The wave, an inviolable force that separates itself from the source, becomes revealed as the euphoric, gentle foam of reencounter, rediscovery, and freedom for new distinct beginnings.

I will always remember when I saw Onça for the first time. His intensity and inner life sparkled in the photo I’d seen of him online as a tribal leader and made me determined to ask who he was to the other indigenous chiefs I knew. But when I found myself in Rio some days later, Edgar, my brother, managed to contact him on FB and learned he was on his way there to attend events connected with a bunch of rich, local people who were launching a line of clothing inspired by the patterns of what his tribe wore to promote their corporation as green. Onça put us in contact with them, and knowing we wanted to see him, they asked us for financial contribution to his ticket and for my brother to host him during the three days he should be in Rio. Since he would stay at Edgar’s house, it was left to us to fetch him at the airport.

While waiting for his delayed plane to arrive, I thought of his face and the shape of his head, trying to abstract them from the indigenous painting decorating his features and from the headpiece he was wearing in the photo I’d seen at the same time as keeping my eyes on the irritating arrival gate, its noisy, abrupt, incessant splitting open to quickly spit out a passenger it would almost crush like a fly when the two doors of it banged back together behind him or her. That mechanic and noisy movement was driving me crazy, but I still tried to spot Onça through any small breach that gave me glimpses of the remaining passengers on the other side, during the split second someone anonymous was burped out of that space of anxiety where those passengers were clinging to the baggage claim with an air of helplessness and defeat as if the separation from their possessions had also exiled them from their identity. I saw no shadow of anyone that could be Onça among those people.

Edgar decided to check another arrival gate all the way at the other end of the airport, but soon I was able to locate on the other side of the gate through a gap between a corner of the opening doors and a corpulent, exiting passenger, a svelte man, casually dressed in jeans and T-shirt yet distinct from everybody in a very different way. There was a fluidity to his silhouette that gave him an ethereal look as if he were the essence of a perfume about to merge with the atmosphere. Instead of being close to the baggage claim, he was apart and looked pensive, perhaps in synchrony with a reality above the possessiveness that ruled the other passengers’ behavior. He and I recognized each other right away when he finally came out. I was in awe of him. At Edgar’s house, I wouldn’t miss any of his movements. He told us everything about his work of reforestation, recovery, and preservation of native cultures, living with urgency but having the confidence of tranquility like counting on all the time in the world to accomplish his rescuing mission because it had been his forever. He’d already planted two million trees with a team he’d trained and inspired many people with his ecological cause. The rare moments we had him free from the million times he must answer his phone or from the functions he should attend were precious. Besides being the most respected shaman in the country, Onça was already a popular figure in the ecological world, he’d been with the Dalai Lama and with the Pope on different occasions.

Edgar allowed three old friends of ours to come to his house and meet Onça because in those days the indigenous leader was seeing people one on one to give them guidance and administer shamanic healings on them. In the bedroom my brother assigned to him, he saw each of us individually, starting with me. I was so sure he would explain my connection with the spirit I’d been repeatedly seeing in the force of ayahuasca that I told him all about it as we sat on the bed in front of each other. His slanted, dark eyes, fixed on me while I talked, remained as inscrutable as the night surface of a lake and I finally asked if he thought that spirit might be a guide to me. Obtaining no answer to my question besides the stillness of his gaze and aware that he was known for his clairvoyance, I, who’d been feeling tired beyond measure, asked if he could see how close to death I was. Over the years I’d been living in this country, having moved here already in middle age, I was drained by the increasing distancing from people I’d left behind in Brazil, the discontinuity between what had been a recent past and what became my present every time me and my family settled in a different place in a new state, and by increasing marital problems. It had been difficult to see angel eyed, sunny Chris, leaving home for college when we’re living in total social isolation in Madison, and having to wait for when he was almost graduating to join him in Boulder only to see him about to leave again for California. This separation had the effect of a slow-release pill on me, and I was also worn out by defending Mia against Jared’s censorship of her pre-adolescent behavior. His anger at me and skepticism of her when I took her out of schools to which she couldn’t adapt and allowed her doing sixth grade online exhausted me. He’d travel on business very often and I was left with her in the cold Madison winter with no one to look for in case of need as I had to drive her over slippery roads and snowstorms in dark evenings to a private instructor or other things. It was a surprise for Jared when she impressed the professionals that evaluated her IQ and her psyche, but I’ve always known she is oversensitive and deep. When we moved to Boulder, she reached the peak of adolescence and with her delicate looks and her fairy harmony became as beautiful as inaccessible. She and I had been inseparable, but she started to behave like I were a stranger or like I’d changed overnight from being a muse to her into someone she was embarrassed of, and as normal as it is, it hurt. My elderly inner clock had made me feel abrupt and random a change that took her an eternity of living, for one’s transformation into a new person, in her case, into a young woman, takes place in the eternal. From having a constant and rich exchange with her, discussing movies, books, art, the mentality of people we knew and their contradictions, we began to live like we were nothing but tenants under the same roof, in a new, unknown city, where we were often alone in the house. She’d give me such an unexpected, unknown image of myself that sometimes I doubted my identity, having to stop still to make sure things around me were solid and the place where I found myself was real.

Adolescents must rebel, but I was still unaware of how much more complex my children’s bicultural situation was in a country where their mother is different from the locals and acts almost contraire to the way they do. The awareness of it came to me through these children having to call my attention in minimal things I wasn’t aware of, like not stopping on other people’s way when walking, not infringing driving rules by disregarding street signs (that I never registered) not getting out of the car to talk to the police when they stopped me and not noticing people I knew in the street. In fact, Chris got in charge of making some discrete sign to me when I should say “Nice to see you”, instead of “Nice to meet you”. But if even in Brazil I was singled out as an outer space creature, here, where people act in a more determined, goal-oriented way, were it not for the locals treating me with kindness and an affectionate amusement, I would feel like an aberration. More than affectionate amusement was, according to Jared—who thought that women were always trying to “touch the hem of your robe” in his words—people looking at me like I were some sort of spiritual entity. I was perplexed with the way an unknown man once approached me out of the blue inside a busy, fancy furniture store in the Midwest, to ask me to pray for him because he’d been diagnosed with terminal cancer. Other situations of the kind made me feel compassionate towards whoever was seeing such spiritual power in small me.

In the first years after I moved to this country with Chris, I was identified to my recent past and could like or dislike the novelty of another culture with the independence of a visitor. But the distance from people who were so close to me in Brazil originated a constant feeling of loss that manifested itself as a chronic and debilitating awareness of death. As that recent past dematerialized through the years with my parents passing, the changes nobody could avoid in both countries like the financial decadence of Brazil, the explosion of the twin towers, the wars in the world and the increasing speed plunging people into confusion, fake news, and disbelief, dissipated what used to be references to me in both hemispheres and the ground under my feet felt half-gone. I don’t know if my definitive move, the magnitude of which, when still feeling like a visitor, I could never fathom, will ever be accomplished. We first lived fourteen years in Jared’s original little town in the Midwest, a place where everyone knew everyone else and were judges of one another according to obsolete patterns of behavior and to a hierarchy of financial power. But I was a mother full time and despite being unable to count on my Brazilian family outside my home nor on friends, the childhood of my kids was one of the richest times of my life; a communion of family exclusivity and single-minded devotion from me. Perhaps I couldn’t have it any other way and my immersion with the children fit well the type of socially isolated life Jared liked to lead, whereas he appreciated my efforts. Those years were also the most harmonious time of our marriage. When Mia was born, I devoted to her full time until she could be sent to her first school and to her and Chris when he wasn’t snowboarding or playing out of the house. As he grew up, made friends, met their families, and told me about them, I realized that other parents treated their children with more distance and less generosity than I treated him and Mia. I was more lenient with them than the parents of their schoolmates were with their kids because I always believed that love and generosity should lay the ground for young people to discover what they’d like to do in life, better than distance and stinginess to arouse lust for material things in them and the need of a job for money’s sake before they have any clue of who they are. I find lust for material things kind of grotesque as a motivation for something as serious as what one should devote to in one’s life, and thought that freer from this lust insofar as I could provide what they wanted with no exaggeration, my children should have the chance to be honest with themselves and make the most of the opportunity to find out what to do with integrity. I would have acted the way I did out of intuition anyway, but my inability to conform to collectivity and be like other parents made me feel like I was going against this whole culture and carrying on my shoulders the huge responsibility of only having myself to justify my way. It wasn’t easy to be this alone, with Jared kind of coming along for the ride and often having heated arguments with me. Between his dry, distant and disciplinarian way of raising children and my instinctive, lenient one, there was no negotiating. No matter where we were living in this country, I was faced with the difficult, inhuman task of making myself absolute because of diverging from what others thought or did, but both Chris and Mia have always been more aware of themselves than those who were intimidated by their parents and distanced from them. There was also more respect and less formality between them and me than I could see between other kids and their parents.

Only after leading a third of my life in the US, distributed by four states and ten homes, I was able to face the fact that as much as Mom, Dad, Edgar and his family missed our coexistence with them, the endlessness of adaptation on my side would be an eternal demand of detachment from me. I never dwelled on the fact that my children’s first culture would not be the same as mine and imagined that after spending a decade here, we’d all be on equal ground. But I became the only foreigner in my little family, often misunderstood because of any slight enthusiasm when talking or the moral indignation I might express in impersonal subjects as if my emotional tone meant personal offenses to them. Jared telling me to not be “so Latin” in these occasions started to get old, but he only stopped when I told him it was “racial” discrimination.

When he and I first met in Brazil, dialogue flowed as if we’d always been living together. He showed no shadow of the Midwest small town conservatism in which he’d been raised or of the American culture’s puritanical inheritance, most people acting as if identifying rule obedience to righteousness and rule ignoring to sacrilege. During the time I joined him in different states of this country before we married, he would be so happy and easy going that I couldn’t see that the fact he wasn’t in his hometown liberated him from the straightlaced context in which he lived and worked. Still, the romantic phase of our marriage lasted a long time for these mercurial days, especially considering that I came to the core of that context in his tiny Midwestern city of origin. Looking back, I can now see that in the same way he loved my informality and unruliness once, he came to conflict with them when his real nature awoke from the slumber of romance and reinstated its love for conventionality and regimentation. I also frustrated his need of control. It was a problem with him the fact that he could never predict what I could do or feel in minimal, ridiculously trivial things like when we once decided to go shopping for a determinate type of plant and I gave some attention to other types. Only now I can see that the anger I’d arouse in him because of little improvisations of the kind, on days we were in no hurry whatsoever, resulted from a desperate need of planning our behavior. He couldn’t stop mentioning my abrupt change of direction in the Magic Kingdom and insisting on the possibility I might in that same way switch my feelings for him to someone else and concluding that living with me was like being on a roller coaster. On my part, I never understood how one could expect to count on the immutability of feelings as if it could be willed by one. I can’t help wondering if people with this kind of expectation ever allowed themselves to really feel anything for the beauty of feelings lies in their happening to one.

Throughout our marital crisis, the depth of Proust’s inexhaustible masterpiece (which I was re reading after the many years elapsed since I first put my hands on it) and the poetic beauty of his otherworldly insights matched the spiritual reassurance I earned from the Vine and helped me to detach myself from the world. As the medicine gave me some peace with the Beyond, A la Recherche du Temps Perdu, analyzing finitude and transcending it, became a bible to me. But even though I’d been living with myself, the dog Chris left with me, and the hope of maturing my creativity by writing and drawing the visions I had from ayahuasca, I said nothing about family matters to Onça. Looking into my eyes, he declared I was a medium and should develop this gift to become a healer, “but your husband is bringing you down because he wants to own you and this way it will not work!” he declared. “You survived difficult times throughout your life and managed to make it because you have a lot of protection. There is an angel by your side, but you must develop your spiritual gift. If you don’t want to develop it, I should remove it from you so it will not charge you but if you do, I will give you some of my power” he decided, impressing me with his power to give power.

Months before I met him, I had a profound experience on a particular night I was by myself in Edgar’s house. I’d been thinking about the ayahuasca ritual I’d taken part of in the previous week, and as I fumbled for the light switch in a pitch-dark kitchen, I heard an angelic voice call my name twice from outside a window that was opened to the night and say, “Come along”. Right before hearing it, a state of bliss had taken over me, dissipating the person I had been until then like unmasking a deceit and making me sure I’d been fooled by that person in not being able to see that there was no error with me nor with the world. The justification I experienced of my whole being was a deep sense of absolution and yet a sensual joy, like I were in sync with some final perfection bouncing off everything. Because it was ultimate, it had an apocalyptic quality that brought butterflies to my stomach.

The apocalypse has been described as a vision of heavenly secrets making sense of earthly realities. The heavenliness of the state I was in gave soul to the ground I stepped on, the air I was breathing, and to every second going by as if time, space, inanimate matter, and my heart, were notes of a chord played in paradise. It felt like the definitive and ineffable secret of God’s love had been unveiled inside me and I was immortal. I thought it was obvious I had blinded myself to this love on purpose as if out of guilt or of some atavistic sort of self-blame, and what had been my existence prior to this experience felt so remote and misguided that it seemed impossible to relapse to it; it was history. I knew it all now, though there wasn’t anything to really “know”. Still, I wanted to identify the thought that had been on my mind when that blissfulness first took over me and remembered that I’d entered that kitchen feeling sure of having contacted spirits in the recent ayahuasca ritual I was part of, this certainty developing into a feeling of liberation that was echoed, in a matter of seconds, by the suavity of the haunting, crystal-clear voice calling me outside.

Before finding the light switch, I’d groped my way to the window and asked the night, “Who is there?” I heard no answer, but the darkness outside showed me a row of non-corporeal entities in dispersed lines, led by the angelic being who’d called me and appeared as a mixture of fleeting strands with blue areas scattered in the obscurity. I couldn’t literally join them and was overwhelmed with awe and plain fear. Back looking for the light switch, I felt the return of the old being I thought I’d disposed of forever, settling back through my body like mud pulling me down. The angst of incompleteness and the void of want reacquainted me with my time-fragmented person and I was back to what had felt gone forever. But by managing to re-experience the certainty that I contacted spirits, hey presto, I was readmitted to heaven for a few more moments.

I never tried to resort to the memory of a certainty I could no longer feel firsthand like I did in that kitchen, but the message of there being a spiritual role I was called to started to build up inside me and I could only feel elated when hearing Onça say I was a medium. His conviction and natural haughtiness were spellbinding, and while he started to perform shamanic healing practices on my head, I couldn’t stop thinking I was a medium. He sucked bad energies from it and after spitting them out the window, he blew smoke on me from a pipe he lighted. He also rubbed some potion of Amazonian seeds and perfume around my throat from a bottle he carried and uttered words in his Indigenous language. When he finished, I asked him how I was supposed to develop the gift of being a medium and he told me to go to the forest for a week. “If you go there I will put you on an ayahuasca diet and teach you” he explained.

I had to ask him whether the artistic reality is not also a spiritual reality to be developed, for since I first took ayahuasca, I started to feel I was growing through my writing and drawing and became more committed to them. He agreed that creativity comes from the spiritual realm but didn’t appear to look at it as an alternative to being a healer, whereas I kept my conviction that art is not just healing for the artist and those who care about it, but is even exorcizing, like Picasso saw it to be. Besides, I wasn’t expecting I’d ever go to the forest by then. Some years earlier, I’d considered doing the difficult trip to attend a musical festival of Txana’s tribe and take Chris and Mia with me. But before Jared’s furious exclamations that I was certifiably nuts for exposing myself and the kids to this venture, I thought twice about it and started to worry about how thin Mia was, her fussiness to eat, the lack of current water in the Indigenous village and the possibility of catching some stomach bug there. To give up something for which I’d mustered so much daring to consider doing demanded from me to find it impossible forever. After all, ayahuasca was self-sufficient to me and I didn’t need going to the forest to take it in the Indigenous ritual. I smiled at Onça’s proposal and asked him what I could do to develop my spiritual gift where I was living in the US. “Look for a trustworthy healer there”, he simply said. His words were motivating, and he became the voice of the truth to me when suggesting I had a path with ayahuasca. To mention the sense of relief I felt with his shamanic praying may sound like self-suggestion on my part, like it happens on the part of people that take placebo instead of a real medicine and start to feel the effects of that medicine. It is more important to mention that beyond shamanism, what was impressive about Onça was his eloquence, his focus, and his unwavering faith. He was polymorphous, looking sometimes like a child, at other times like a determined man and at still other times like the ancestral being he said he incarnated. “A very wise leader of my people who came to help” in his words. “Incarnate healers come from the stars and can access the spiritual world” he explained, when sitting next to me at a restaurant where Edgar and a few friends took us to eat lunch. “Even if they come from different places, when they meet, they get connected forever” he declared, planting his hand on my shoulder in front of everyone at the table and making me feel like I was being blessed by a saint.

I’d known for a long time the people he saw after me at Edgar’s house, and hearing what he told them about themselves to their faces at first sight, I only became more confident in his vision. Besides having a reputation of healings and opening ways to people with his shamanic practices, Onça was reverenced for his determination to save the rainforest from the rapacity of money-grabbing people in Brazil. When he told us stories that interweaved facts with ayahuasca revelations, myths, the healings he’d been able to do, the miracles worked by the elders of his people, his ecological mission, and the several times when local lumber men were prevented by angelic interference from doing away with him, it was difficult to follow his words through the long pauses he made, his different way of articulating ideas, and the supernatural quality of what he reported. Because he felt ultimate to me, I couldn’t discredit what he told us, but unable to fully believe in it, I felt bad for not having total faith in someone I found so superior to myself. The conflict between being carried away with him and resisting his stories made me feel incoherent. I am aware I tend to look at people beyond their context and when I bonded with Jared, I never thought that the radical difference between our background could come between us. More than anyone else, I saw Onça as a self-creating being who was above the tradition of his culture and any other type of context. He was fully present and carried away at the same time, steady and under the grip of passion, seeming to live between all and nothingness like walking on the edge of an abyss, only him counting. Unguarded against the future, Onça was the focus of courage, an infinitude of presence that only fits within the hands of God and only works from them. Courage is synchrony with destiny; it is a contact with eternity for it is whole regardless of what follows from it. An act of courage exiles even the irreversibility of death itself to nonexistence. Surviving it or not, whoever responded to its call outgrows the limits of his or her being and is forever a hero.

Onça told us that he didn’t like the cities and in general only traveled to attend ecological events overseas, but I knew that no matter where, I’d take my children to his presence one day.

After a year during which I continued to do my individual, creative work, I also needed to see him again, hoping he might give me a direction or renew the invitation to teach me. I’d found an intelligent, mystical lady in Boulder I had sessions with and don’t include her in the skepticism arousing people whose speech is a mumble jumble of pseudo-physics mixed with spiritual terms trying to transform transcendence into something that can be under control, teachable, and even promising of money, which is referred to as “abundance” in veiled messages of earthly success. When thinking about the inspiration from the real mystics—those to whom detachment from material things, success, and recognition meant communion with God, those who were proud to suffer and survived it by miracle— I thought it made room for a disguised egotism of a mere will to power in Western “mysticism”.

But nothing is more fascinating to me than the encounter of spiritual and human nature all the way from Jesus Christ to artists, shamans, monks, and all those who keep in contact with an essence above all transiency, a nudity before life. The poem If, by Rudyard Kipling, is the best expression of this communion with one’s truth despite the momentary applauses and flops that hide foreverness with fleetingness, essence with contingency, especially in the lines:

“If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster

And treat those two impostors just the same”

It was easy convincing the kids to search for Onça all the way in the jungle. Chris is an eternal adventurer with insatiable curiosity and had already visited the Hunikuin tribes when graduating from school, whereas Mia had been wanting to set foot in the Amazon ever since we considered going there for Txana’s festival. Onça’s village was tucked away on the border of Brazil and Peru, and since one of the Brazilian airports where we’d have to switch planes was closed because a fire had broken near it, Chris and I figured it might be easier to reach our destination by going from LA directly to Lima and work our way from there. This commonsensical idea wasn’t grounded, and I never thought that the Peruvian path to Onça was a trillion times longer and harder than the Brazilian. Once we left the main cities, it was impossible to program the continuation of the trip online and Chris had to figure out our way as we got gradually ejected from the “civilized” world like hanging off the edge of the planet by a string. In Brazil, we would reach the nearest community to Onça’s village by a bush plane and from there only take seven hours in a canoe up the river to arrive at our destination. But in Peru, the community of natives where the same type of plane dropped us was much farther from it and we must travel in the canoe the whole day, cross the border with Brazil in the water and still navigate sixteen hours up the river.

It was very hot when we disembarked in the Peruvian community, and I was far from imagining how long we’d still have to go from there. The natives were dressed in poor, civil clothes like in leftovers of civilization denouncing the destruction of their original culture, the thinness of their bodies, and their apologetic attitude. A group of them surrounded our plane when it landed in an open field of earth, some distance away from their homes. Red hot dust came off the ground when we walked and as I took a few steps away from the plane, all the discomfort to come, which I’d been able to push out of my mind that far, felt like a ton of bricks falling on my head after I asked someone where I could go to the bathroom and was informed there wasn’t one. “Things are natural here”, I was told, and it should only be the beginning of the lack of facilities I must endure. The thought of it made my knees about to collapse under the ever-hotter sun, but as I dragged myself close to the kids, all the heaviness pulling me down was dissipated at the instant sight of a rebellious puppy squirming in the hands of a local who seemed to have gone there to watch the plane with a bunch of other people. The little creature was white, cuddly, and comically fierce in its attempts to get free from the woman who was juggling with its restlessness; I couldn’t take my eyes away from it and asked her permission to hold it. But the little animal was determined to be let loose, and when I started to kiss his head—it was a little “he”— accommodating him between my shoulder and my neck, he growled so loud that the contrast between his anger and his loveliness made him even more irresistible. Only innocence can be endearing in wrath, and in joy, it is the joy of joy itself. I fell in love with the puppy. When he finally jumped to the ground, the world was transformed into a stage for grace under his small, daring, and soft paws that knew no danger. All my anxiety with the difficulties ahead disappeared, and by the time Mia and I went somewhere in the shade to wait for Chris hiring a canoe and a canoe man for us, I was sure that if I found a puppy in Onça’s village, I’d be in paradise. The wordless contact with an animal, the silence of love in its scent sends me. I couldn’t stop thinking about the puppy I’d met and was forced to realize that the wish of finding him again in another of his kind had taken over me; I was replacing the need for a shaman’s spiritual orientation by a sudden call that only led to itself, the immediacy of satisfying it being beginning and end at the same time. A completeness that, like an instant blessing, liberated me from all afflictions. I knew that regardless of what may come, I’d find plenitude in the contact with another puppy and the likelihood of finding one in Onça’s village did not leave my mind as if I were holding on to a charm of good luck.

After managing to urinate behind a tree, I reunited with Mia in the shadow and soon Chris showed up to fetch our bags to place them in the canoe. He wrapped them in thick plastic material and put them in the center of the vehicle, behind the bench he told us to sit on when it was our turn to board. I had not expected our transportation to be so flimsy, small, and lower than the shore. Besides having to step down to reach its wobbling, escaping floor one had to be careful to not capsize it while balancing oneself to also avoid falling in the water. After Mia and I settled in Chris took the back seat and the boatman, who was a very old native whose eyes were like two slits between series of horizontal wrinkles, stepped on the bow. While the canoe’s engine pushed it up one of the tributaries of the Amazon River, I was at one with my children over the most genuine, rustic, and organic ground the planet has to offer and felt more rooted than ever, not even minding the fact that our old boatman showed no notion of time nor distance. No matter how many hours we’d already travelled in the river, whenever he was asked how long we still had to go to reach Onça’s village, he’d answer, in a faint tone and with an air of having given it a lot of thought: “Three hours”. His engine turned out to be very slow and every canoe coming our way quickly left us behind. Besides, it appeared he couldn’t see any of the half-submerged trunks of trees he should deviate the vehicle from to avoid a clash with them and a flipping of it over us with the engine working, which could be serious. He was forced to swerve it abruptly when Chris alerted him about those obstacles, and it would end up slamming against the riverbank. In those moments we had to step out in the water to help releasing it before getting back in to continue. Because of these stops, the length of the way, and the slowness of the canoe, we had to spend two extra nights on the way. While we were on the river, Chris played with the idea of setting up some sort of travel agency offering exotic adventures, like the trip we were taking, to give parents and children the possibility of rediscovering themselves and renewing their bond. Only after being back in this country, I became aware of the risks we took by riding in that canoe. While we were away, Jared had talked with an activist who’d been there and he mentioned the possibility of assaults from drug trafficking pirates hiding in the shores and the likelihood of collision with other badly driven canoes coming from the opposite direction. But during our ride, I was leaning on our luggage and merging with the air I breathed. Sometimes, I dozed off, and whenever the old man slammed the vehicle against the bank of the river, I’d wake up with the rush of water that had accumulated in the floor flooding through my feet and behold, with gratitude, the blissful luminosity of the green leaves of trees between me and the bright blue sky above.

I’d sent Onça several messages to obtain his permission to visit him that time but only earned it when finally spotting him on FB and daring to ask yet again if I could do it with my children. After some hesitation, he warned me we had a window of time before a television documentary crew arrived in his village to film a special program about his culture. Because of the closeness I’d felt to him, I was expecting he would even think I’d finally come to my senses by wanting to see him in the forest. Instead, I felt I was imposing myself. But it was July, the only time when both Mia and Chris were free to do that trip with me, besides the fact I’d been living in function of finding the path which a year earlier Onça had convinced me to follow. I’d been questioning myself to infinity and bearing with the restlessness of a spiritual search which is something whose closure always lies ahead of one, like the line of the horizon. To justify traveling all the way to the jungle with no real invitation from Onça, I had to keep remembering Kierkegaard’s assertion that he would go anywhere in this world to meet someone like “the knight of faith” he created in his heartfelt description of a genuine, humble character, capable of receiving whatever comes his way as a gift.

Eleonora Duvivier

Eleonora Duvivier was born in 1953 in Rio de Janeiro, where she attended the Lycée Français. She comes from a family of artists and has held two exhibitions of oil paintings in Rio. Having studied philosophy at PUC (Brazil) King's College (England) and Boston University ( USA) she started giving priority to verbal thinking over visual images for expressing her ideas. She has written her books in English but she also contributes to a Brazilian site with chronics she writes in Portuguese.

Eleonora has been living in this country for thirty years. She currently resides close to her grown-up children in Southern California.

To learn more about Eleonora, check out her website: https://www.eleonoraduvivier.com/

The heat of the sun was more intense than I’d ever felt before and we either held umbrellas or, when napping, managed to secure them over our head from the floor of the canoe and still had to refresh ourselves now and then inside the water. But being behind schedule stopped to interfere with my plenitude as we traveled between rows of immense trees standing on each side of the river like protecting angels guarding the way to heaven. Floating on the primordial water of their millennial soil with my offspring and being literally in the same boat with them was beyond sharing a country, a land, a time, or a culture, like we were in the beginning and reason of life together.